- Europe

- Etats-Unis

- Economy

Meloni’s Industrial Gamble: Between Liberalism and Sovereignty

Marco Malaguti

Marco Malaguti is a philosophy researcher, columnist and blogger. His work focuses on Central European education, philosophy and politics. As an associate researcher at the Centro Studi Politici e Strategici Machiavelli, one of our member foundations, he brings valuable expertise to bear on issues relating to the ideas and cultural and political dynamics of this region.

In the complex situation currently facing the European Union—caught between the consequences of the war in Ukraine and the constraints of the so-called Green Deal imposed by the European Commission—the current Italian government has attempted to implement an approach that combines fiscal discipline, production incentives, and reindustrialization, all without departing from the principles of a market economy.

A Selective Liberalism: Between Fiscal Rigor and State Intervention

Since the beginning of her term as Prime Minister on October 22, 2022, Giorgia Meloni has made no secret of the economic direction she intended for Italy. After years under technocratic governments ideologically aligned with Brussels, the Italian economy showed an urgent need for reform—reforms that, while avoiding the pitfalls of improvised economic populism, could deliver immediate impact in an increasingly strained context. Meloni’s economic policy—designed and implemented with the support of Economy Minister Giancarlo Giorgetti—has redefined the country’s economic priorities. While formally adhering to EU-imposed parameters, the government has sought to reinterpret them from a national interest perspective, prioritizing the health of the Italian economy and its reindustrialization.

Credit photo : Antonio Masiello / Getty Images

This strategy aligns with the longstanding ideological stance of the Prime Minister and her party, which for years have advocated for a stronger focus on the individual economies of EU member states, rather than blind adherence to EU budgetary constraints. Given Italy’s heavy dependence on exports, the challenge facing Meloni’s government has been to combine a liberal trade approach with a renewed respect for national borders—a form of liberalism with the nation at its center, in contrast to a limitless globalist and free-market paradigm.

For all Italian governments of the so-called Second Republic, the core economic dilemma has remained consistent: how to reconcile fiscal constraint with tax relief for businesses. Italian companies have long suffered from a particularly burdensome tax regime—the corporate tax rate, for instance, stood at 27.9%, comprising a 24% IRES (Corporate Income Tax) and an average 3.9% IRAP (Regional Production Tax), nearly eight percentage points above the OECD average of 20%. Such conditions have offered little incentive for domestic entrepreneurship to remain within national borders.

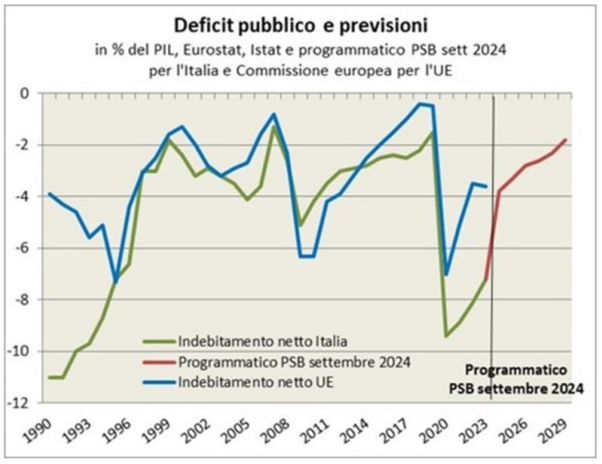

After coming under scrutiny in 2024 due to an excessive deficit procedure, Italy’s public deficit has been significantly reduced under the new government—from 7.2% in 2023 to a projected 2.8% in 2025—thus fully returning within the limits established by the Maastricht Treaty. This result can largely be attributed to the abolition of two measures enacted by the previous government under Giuseppe Conte: the “110% Superbonus” and the “Façade Bonus” (both were Italian tax incentives that allowed homeowners to deduct up to 110% of renovation costs, including energy efficiency and façade improvements. Though they boosted the construction sector, the government reimbursed these costs through tax credits, dramatically increasing public spending. This led to a significant rise in Italy’s budget deficit and public debt.

Taxation for Industry and the Reshoring of Italian Enterprises

At the same time, in order to relaunch the competitiveness of Italian businesses, the government sought to address one of the most pressing issues: the heavy tax burden. For example, the corporate income tax (IRES) may be reduced by approximately four percentage points for companies that commit to reinvesting at least 30% of the profits saved in the previous year. This measure has been welcomed by Confindustria (General Confederation of Italian Industry, which is the main organization representing manufacturing and service companies in Italy). Moreover, new artisan enterprises and small businesses—critical components of the Italian economy—will benefit from a 50% reduction in social security contributions to the National Social Security Institute (INPS) for a period of four years.

However, the need to boost exports could not rest solely on supporting the industries currently operating within national borders. It also required a strategy to bring back businesses that had previously relocated abroad, discouraged by an overwhelming and burdensome tax system. The reshoring of Italian industries has, from the outset, been one of the cornerstones of the Meloni government’s industrial policy, as Minister of Business and Made in Italy Adolfo Urso said:

“In an era of de-globalisation we must think about reshoring companies.”

To this end, the government introduced a provision last year that commits to a 50% reduction in the taxable base for IRES and IRAP for companies that relocate their economic activities from non-EU countries back to Italy. This measure allows Rome to maintain good relations with European countries—especially in Eastern Europe—where many Italian companies have recently relocated, while simultaneously curbing the outflow of wealth and industrial know-how to the People’s Republic of China and other nations of the Global South.

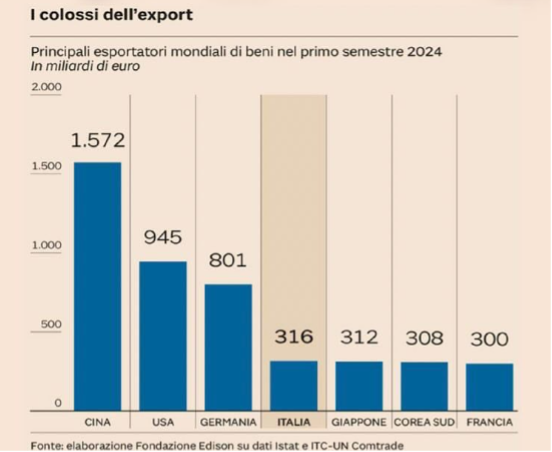

These measures have already begun to yield positive results. Italy has increased its trade surplus with the United States (reaching €34.7 billion), thanks primarily to its manufacturing sector: mechanical engineering (€10.8 billion), food and beverage (around €7 billion), textiles (over €5 billion), and automotive (€3.5 billion). As a result, Italy has now surpassed Japan, becoming the world’s fourth-largest exporting power, with exports valued at approximately €316 billion.

Industry 5.0: The Italian Path to Sustainability

Building on these choices, the Meloni government has made it a priority to protect Italy’s traditional industrial strengths—particularly in mechanical engineering and textiles—without neglecting key sectors such as food and wine, automotive (especially in its luxury segments), and high-tech industries. The Prime Minister has repeatedly emphasized the importance of attracting new investments while also making strategic use of the “golden power” (special law that grants the government the power to prevent the sale of domestic companies deemed strategically important to foreign enterprises), who give mechanism to safeguard national sovereignty over companies and knowledge considered vital to the country’s strategic interests.

Increased investment in the defense sector—where Italy boasts leading firms like Fincantieri and Leonardo—is also expected to play a pivotal role in the government’s vision for industrial revitalization. Protecting the domestic automotive industry, one of Italy’s most prestigious sectors, has led the Prime Minister to directly challenge European policy on electric vehicles. On April 11th, the government formally requested the suspension of the Green Deal as it pertains to the automotive sector, criticizing the European Commission’s approach as excessively dogmatic and punitive. The government views the Green Deal as promoting an unsustainable trajectory that ultimately benefits economic competitors outside the EU—countries less inclined to embrace the climate alarmism currently in vogue across the continent.

In essence, Giorgia Meloni’s approach can be interpreted as an attempt—still partial and in progress—to drive the reindustrialization of Italy. While the process is ongoing, it appears to be aligning the country more closely with the economic strategies of the new Trump administration in the United States, which seeks to decouple from the Far East and reassert sovereignty over its economy and innovation capacity—without resorting to simplistic, neo-socialist populism. As always, it will ultimately be the markets that render the final verdict.